A slab of wood in the waterfalls and a drive in the wilderness

The Wooden Plank in the Rapids

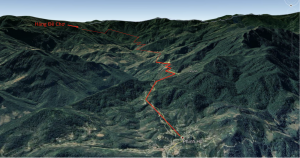

I don’t know how many times I’ve had to grip the throttle of my motorcycle in the past three hours, but by now, my hand feels numb. My thighs ache from holding my legs out to balance on the bumpy, gravel road. A suffocating heat radiates from the Yammie—my nickname for the motorcycle that has accompanied me for over 10,000 kilometers on the open road. It has endured so much, running in first gear for three straight hours.

Should we give up? I turned to Ruben, my travel companion, asking him the question.

“No, we’ve come too far… That last 12 kilometers had nothing but dirt, rocks, a few drops of blood from the times we’ve fallen, and the fear that we wouldn’t make it through this stretch.”

But then, with some extraordinary effort, we finally reached our destination after the fifth hour of this 12-kilometer journey. To reach where? You might ask. And I’ll answer: to nature—or what we call nature. To experience something wild, untouched by humans and the chaos of Hanoi.

Once we arrived at the base of the waterfall, we set up camp. But then, a new fear crept in: firewood. With only 30 minutes before nightfall, firewood became a matter of survival. But at the foot of a waterfall, dry wood is hard to find.

At that moment, you switch into survival mode. We scoured the bushes and rocks, and by some miracle, we found a pile of wet pine planks washed up by the stream. For those who don’t know, pine planks, even when wet, can still catch fire. Ruben and I exchanged a look, as if we had struck gold.

But wait, aren’t we in a forest, with no human presence for miles, within a 25-kilometer radius? Why are these planks so neatly cut and arranged? I sighed, watching the pinewood catch fire and slowly dispel the cold of the night. There was only one explanation—this area is involved in illegal logging. As soon as that thought crossed my mind, I saw a flashlight beam shining toward us.

“Who’s there?!” I shouted, gripping the knife at my side.

A tall man appeared under the moonlight, holding a homemade 2-meter-long rifle. His face was cold.

“Shut up! I’m hunting night weasels. Your shouting scared all the game away!”

As you can see, no matter how far you try to escape in this land, you’ll always find traces of human presence. Finding a truly untouched place in Vietnam, free from exploitation, is almost impossible.

“Golden Forest, Silver Sea”

At the Central Party’s History Research Conference, on November 28, 1959, President Ho Chi Minh said: “Our country has golden forests and silver seas, and our people are diligent.” The phrase he coined emphasized the importance of protecting the country’s precious natural resources.

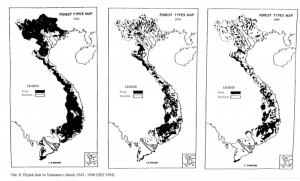

Unfortunately, the reality of forests in Vietnam between 1943 and 1990 tells a different story.

Chart: Changes in forest cover in Vietnam from 1943 to 1990. Black represents forest cover, while white indicates non-forest land. Source: GEF, 1994

Due to the impacts of war and the subsequent population development of a country in post-war reconstruction, we made a trade-off. The most noticeable changes were in the Northwest, Central, and Central Highlands regions.

Recognizing the threat of deforestation, the government implemented many policies in the 1980s and 1990s to curb logging, such as bans on timber exploitation. By now, forest cover has returned to near 1940 levels, but much of it consists of “production forests,” i.e., plantations of acacia and pine for economic purposes. What’s worth noting is that these replanted forests have much lower biological value compared to the original, pristine forests we once had, as diversity has been replaced with just one or two tree species.

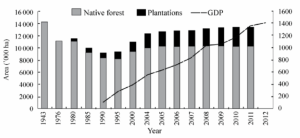

Chart: Reforestation efforts to increase forest cover from the 1980s to 2012. Gray represents natural forests, while black represents planted production forests (Kellas and Pham, 2013).

Becoming “Silver Forest, Golden Sea”

The trade-off between environmental destruction and economic development has always been a complex issue. Ensuring that 90 million people have jobs on this narrow piece of land inevitably requires some sacrifice in terms of natural resources.

At times, these sacrifices leave long-term consequences. On our way back from Hang De Cho, we passed by Xuân Sơn National Forest. Around the forest, valleys that were once covered in trees have now been transformed into farmland.

In 2016-2017, a flash flood swept through the area, destroying roads, houses, and the fields of local people. Now, to reach the ethnic minority village, Ruben and I had to leave our bikes and walk through a forest trail for about 30 minutes. Along the way, we met farmers carrying their produce to the market, their exhaustion and sorrow evident. “We don’t have much left. Our few rice fields that used to feed us for the whole year have all been washed away. My son had to go to Hanoi to work in construction to make a living,” shared one farmer…

What Now?

I hope my small story will spark discussions on rural economic development and forest conservation. This issue is not only happening in Vietnam but in many countries around the world. If you feel disappointed right now, I understand. For me, the light at the end of the tunnel is that this issue is well understood by government agencies, and many progressive policies are being implemented to turn the tide.

To answer the big question, “What now?”, we need knowledge—the knowledge to determine the best way to balance the scales between human/ economic needs and the environment. In addition to raising awareness through media campaigns, I also encourage young people to engage deeply in research on economics, environmental issues, and forest management, so they can contribute to long-term policy changes.

Nguyễn Vũ Bảo Nam is currently a research specialist at the International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT), an organization that provides policy recommendations on climate-adaptive agriculture, disaster prevention, and ecological management.